AI And The Five Stages Of Grief

Some ideas I’ve had rolling around in the back corners of my mind for years, and even decades. Theories and kernels of narratives that come to me, inspired by a wide range of circumstances. In part inspired by comedians and writers I admire, I started making it a point to record these ideas as often as I can. Some of the ideas though have stood the test of time, even without writing anything down, and even if I don’t give them conscious thought regularly. I decided yesterday to try something: I would use ChatGPT to facilitate expanding on and expressing one of these ideas. So below is the result of about 10 minutes spent using the AI tool to flesh out my theory that humanity as a whole has been acting out the five stages of grief over the course of the species’ history:

Grieving Our Mortality: Humanity’s Journey Through the Ages

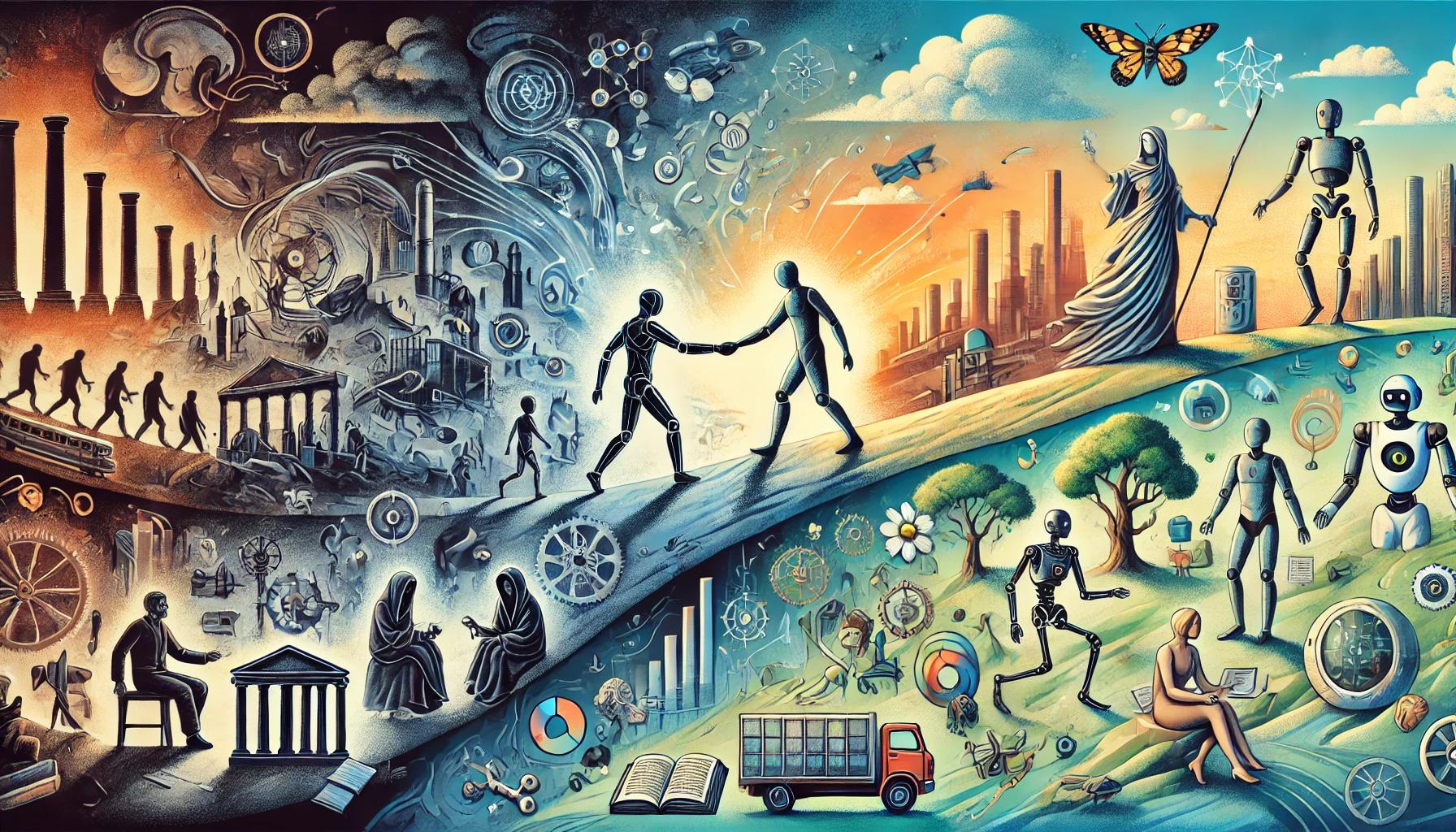

For a long time, I’ve been intrigued by the idea of mapping the stages of grief onto the trajectory of human civilization as a way to understand how we, as a species, have grappled with the unsettling knowledge of our own mortality. Each epoch of history—whether it’s the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, or the Industrial Revolution—reflects a different emotional response to this profound reality. Recently, I decided to test how AI could support me in fleshing out this concept. The rise of AI has sparked widespread fear: some worry that it will displace human creativity, while others see it as a tool that could be used maliciously. But what if we reframed it as a constructive collaborator—a tool that can help us explore, refine, and deepen our own ideas? The following framework emerged from this very experiment: an exploration of how the 5 stages of grief might map onto the historical journey of human civilization, illustrating our species’ struggle to confront its own impermanence.

1. Denial – The Dark Ages and Early Medieval Period

In the aftermath of the collapse of classical civilization, humanity entered a period of intense denial. This was a time when Europe turned inward, shunning knowledge and clinging to rigid religious ideologies as if rejecting the inevitability of decay and death. Civilization, in a sense, refused to acknowledge its own mortality and fragility by building narratives of eternal salvation and divine protection. The denial of human mortality is symbolized by the mythic and mystical worldview that dominated this age, where suffering and death were externalized as punishments or tests, rather than natural parts of existence.

2. Anger – The Crusades, Wars of Religion, and Colonial Expansion

The anger phase is expressed in humanity’s violent attempts to assert control over its mortality by conquering new lands, converting “heathens,” and imposing order. The Crusades and later religious wars, as well as colonial conquests, represent civilization lashing out at perceived threats—both external (other cultures) and internal (the chaos and unpredictability of life itself). This rage is an expression of humanity’s deep frustration at its own powerlessness against death and oblivion. The desire to spread one’s faith and culture, often at the cost of others, reflects a deeper, primal anger at the limits of human life and legacy.

3. Bargaining – The Renaissance and Enlightenment

As humanity rediscovered classical knowledge and embraced reason and science, there was a collective bargaining with mortality: “If we can understand the universe and master the natural world, perhaps we can extend our lives, our empires, our civilizations.” The Renaissance and Enlightenment are characterized by attempts to strike deals with fate, creating art and literature that immortalize human achievement, and pushing scientific boundaries in the hopes of delaying the inevitable. The search for meaning, knowledge, and the development of utopian ideals reflect humanity’s deep wish to transcend its mortality by leaving something permanent behind.

4. Depression – The Industrial Revolution and Early Modern Era

This era brought incredible technological progress, but also profound existential despair. As machines replaced human labor and cities grew into impersonal metropolises, humanity confronted a deep sense of meaninglessness. The beauty and grandeur of the pre-industrial world seemed lost in the relentless march of progress, and the romanticization of nature in art and literature reflects a mourning for a simpler, more harmonious existence. People felt more like cogs in a machine than beings with intrinsic value, prompting existential crises and early movements of disillusionment, seen in the works of writers like Dostoevsky and Nietzsche.

5. Acceptance – The Late Modern and Postmodern Era

Today, humanity stands at a precipice, attempting to come to terms with its own impermanence. With the threat of climate change, nuclear weapons, and dwindling resources, there is a growing awareness that humanity might not survive forever—that our species is just as mortal as the individual human. The focus on sustainability, mindfulness, and creating long-lasting societal changes reflects a tentative step toward acceptance. But it is not a passive acceptance; rather, it’s an urgent reckoning with the consequences of our past denial, anger, and bargaining. We see it in movements that seek to preserve what’s left—our environment, cultures, and shared humanity—in the face of an uncertain future.

Epilogue: Toward True Acceptance?

True acceptance may involve humanity coming to peace with its own transience, valuing the present, and creating meaning without the promise of immortality. This could mean embracing the idea that, like every other species, our time will eventually end. Whether we reach that stage or continue to cycle through the previous ones is the existential question of our era.